British medical students Tom Nash (left) and Ashley Davies tend to a sailor with third-degree burns

Sandwiched between a bookcase of medical literature and a stack of promotional t-shirts, an elderly man sits slumped in a chair, one frail hand gripping the mask administering his daily fill of oxygen.

Opposite him, behind a small curtain, a sailor who suffered third-degree burns when a boat engine blew up grits his teeth as the dressing covering most of both legs is gingerly replaced.

Here, in this tiny charity-run clinic on Antigua’s south coast, this is just a regular day for the volunteer medics operating where government facilities fall short.

Amid gasps of breath, Sinclair West, who the team believes probably has lung cancer, says he would be dead without this place.

The former security guard is one of about 1,000 visitors who flood annually into the donation-dependent clinic, open and on call almost every day of the year.

Familiar number

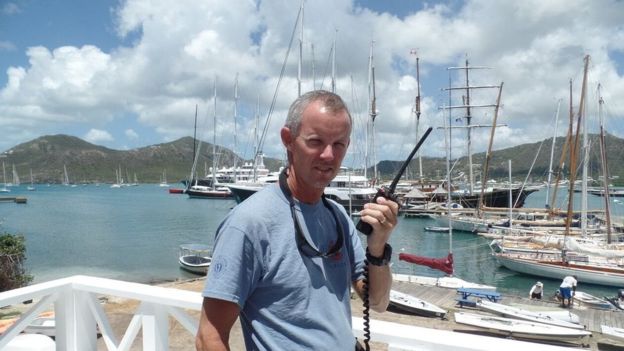

In addition to providing maritime emergency coverage across 500 sq miles (1,300 sq km), the Antigua & Barbuda Search and Rescue team (ABSAR) has become a lifeline for those on land too.

People in the sailing hub of English Harbour, which attracts thousands of tourists each year, know better than to call 911 in the event of a crisis. The seven-digit phone number to reach ABSAR has become as familiar as their own.

By the time a state ambulance has negotiated its way across potholed roads from the capital St John’s, it will have taken 25 minutes to get here, inconvenient for a victim of a minor fall, fatal if it is a heart attack.

Mr West has been a daily fixture at the clinic, a short walk from his house, for months.

“He has something in his left lung,” ABSAR director Jonathan Cornelius explains, “and he can’t get enough oxygen, so he comes and spends several hours here a day using ours.

“The hospital won’t facilitate giving him oxygen at home.

“During his last stay there, they put a tube in his chest which they removed before discharging him, leaving an open wound. We spent three months dressing it for him.

“His is not an isolated case,” Mr Cornelius continues.

The reason? A woeful lack of resources and, some say, a lack of care.

“We were quite shocked to see how poor the facilities are at the hospital,” remarks a visiting medical student, “and the staff really didn’t seem in a hurry to do much.”

Search and rescue

Antigua’s chief medical officer Dr Rhonda Sealey-Thomas said efforts were under way to augment the hospital’s emergency services, including extra staff and the establishment of a dedicated urgent care centre, while $10m (£7m) had recently been spent on new high-tech equipment.

ABSAR also responds to about 30 search-and-rescue calls a year, anything from missing scuba divers and overdue fishing boats to yachts marooned on reefs, fires and even seasickness.

It also plays a vital role in the numerous annual sailing regattas Antigua is famous for.

Yet it does not receive a cent from government, save for duty-free concessions on equipment, and is entirely reliant on donations and a smattering of fundraising events to bridge the annual $75,000 it needs to function.

Generous benefactors have helped ABSAR acquire its ambulance, two boats and fire truck. Its miscellany of medication is gifted by visiting yachts.

Every single one of its dozen responders is unpaid.

And now ABSAR faces an uncertain future. Without more manpower, it will soon be forced to cut back on its crucial clinic services.

‘Desperate need’

“We’re a victim of our own success,” Mr Cornelius admits.

“More and more people come to us every year for various treatments. The problem is, they expect us to run like a hospital and we just don’t have the resources.”

US-trained Mr Cornelius has been working as a paramedic for two decades, initially providing island-wide coverage alone with a pick-up truck.

He established Antigua’s emergency services himself, creating the clinic after getting frustrated “sewing people up on the dock”.

He regularly works an unsalaried 90-hour week, tending to most calls personally.

“We desperately need volunteers willing to show up for weekly training and be available for call-outs.

“Not everyone enjoys going out on the water at 03:00 in a four-metre swell and 35 knots of wind, so they have to be committed – and half crazy,” Mr Cornelius adds with a wry grin.

Volunteer Kiana Harrigan, 18, says she has dreamed of being a paramedic since she was a child, and testifies to its rewarding nature.

“I always wanted to help people and it sounded so exciting compared to being a nurse,” she says. “You see the look on someone’s face after you’ve helped them and they are like, ‘Thank God for this person.”

This story is credited to http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-36152493